Written by: VEDAT ÖRÜÇ / HASAN BERK AKKOÇ

Translation: SEBLA KÜÇÜK

On the morning of November 6, as I was walking to the subway station to go to work, I saw a group of people gathering near the traffic lights on Söğütlüçeşme Street. As I got closer to the crowd, I could see a police officer setting up barrier tapes around the scene. There was a young man in his 20s lying on the ground next to his overturned motorcycle and he was waiting for medical assistance. I could understand from his coat that he was a courier on his way to deliver an order. People walking by were discussing why the accident might have happened. But the mystery could be solved just by looking at the words written on the top box on the motorcycle: “At your door within minutes.” It was obvious that he exceeded the speed limit to deliver the parcel as soon as possible.

motokurye vedat oruc 1The motorcycle courier who had an accident in Söğütlüçeşme, İstanbul on November 26, 2021 (Photo: Vedat Örüç)

motokurye vedat oruc 1The motorcycle courier who had an accident in Söğütlüçeşme, İstanbul on November 26, 2021 (Photo: Vedat Örüç)

This scene has become a classic on the streets since the beginning of the pandemic. The insatiable greed of online sales companies means we see more couriers in the traffic. Nowadays there is a delivery courier riding on every street as they have become essential for customers due to lockdowns and curfews. They deliver food, water, documents, etc. in a very short time but there is a price for that: poor working conditions. They don’t have any fixed working hours, weekend holidays or annual leaves…

900,000 MOTORCYCLE COURIERS ON THE STREETS

Although the exact number is not known, trade unions estimate that there are more than 10,000 motorcycle couriers in Istanbul. The number of all couriers in Turkey is estimated to be as high as 900,000, including informal couriers. With the pandemic, the booming delivery industry also saw an increase in fatalities among couriers. Dozens of them are involved in traffic accidents as they are forced by companies to “make deliveries fast”, and many lose their lives in these accidents.

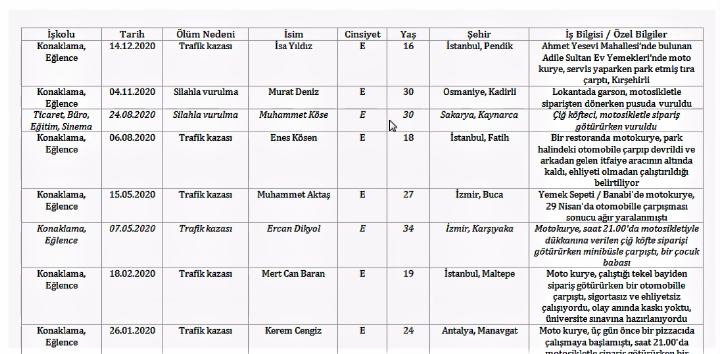

The exact number of casualties is unknown, but the tally held by Anatolian Motorcycle Couriers’ Federation demonstrates the severity of the situation. Approximately 227 couriers died at traffic accidents between March 2020 and June 2021, including many young people in their 20s. According to the data published by the Assembly for Occupational Health and Safety (İSİG), almost half of the couriers who passed away in 2021 were in their 20s.

motokurye 2Identity information of the couriers who died, according to data published by İSİG

motokurye 2Identity information of the couriers who died, according to data published by İSİG

THE STORY BEHIND THE BOOMING DELIVERY INDUSTRY

Covid-19 pandemic had a major impact on the consumers’ shopping habits all around the world. Unlike many other industries which receded during the pandemic, as more and more people turned to online shopping due to curfews, the delivery industry saw a significant growth in many countries, including Turkey where it had been fledgling. Therefore, motorcycle couriers became the most important group of workers in the system, by delivering goods from e-commerce retailers to customers.

The “Online Customer Habits” research published by UPS shipping company shows that globally e-commerce sector has grown by more than 50 percent. Since the beginning of the pandemic in Turkey, mobile retail sales have increased by 200 percent, and the demand on online channels of national chain stores went up by 150 percent. According to the data of Ministry of Commerce, the e-commerce volume in the first half of 2021 was 161 bn TRY, which was 75.6 percent higher as compared to the previous year. The number of orders also went up by 94.4 percent from 805.7 million to 1.654 billion.

This drastic change in the e-commerce industry and social relations not only affected the commerce sector, but it also led to an increase in the labour demand in mail and courier services. The sociological transformation brought by the pandemic placed courier services in the spotlight. Multinational companies boosted investments in courier services, which gave birth to global giants. Meanwhile, many Turkish fast delivery companies expanded their operations abroad. These developments also affected the relationships of employment in the industry: the labour demand went up – particularly cheap labour became highly sought after. Employers, looking for ways to slash labour costs, found remedy in new business models, such as “self-employed couriers”, also known as “owner-drivers.”

SELF-EMPLOYED COURIERS: “BE YOUR OWN BOSS!”

Companies which offer shipping services, online shopping platforms and food businesses resort to “owner-driver” model as a way of outsourcing their delivery operations. In this model, companies, instead of hiring their own delivery workers, buy services from self-employed couriers who have their own delivery companies. With this model, companies can move beyond the traditional employer-employee relationship, and cut down on labour costs.

In this system, couriers establish private companies, and handle delivery operations on behalf of the delivery service companies but they use their own vehicles. The delivery service companies often publish advertisements for new labour promising that couriers will “be their own bosses.” Couriers work under this model instead of working as an employee of the company under a contract. However, this new form of employment relationship often means couriers become fully dependent on delivery service companies in terms of working hours, revenues, job security, etc. The model, which is also used in Europe, the US and Canada, is denoted as “fake self-employment” because employees are still liable for the main duties described in a standard employment contract, such as being dependent on the employer, following the orders and instructions of the employer, fulfilling assigned duties and being paid in return for the work done.

WHAT DOES BEING AN OWNER-DRIVER MEAN FOR WORKERS?

In this employment model, couriers do not have a specific work place, such as a store or warehouse. Instead, couriers park their motorcycles at a convenient spot in neighbourhoods, and follow the instructions to be sent by the delivery company via an application on their smart phones. The application assigns online delivery requests submitted by subscribers to the nearest couriers. The delivery companies merely act as an intermediary, and receive a commission for their services. Couriers work under the conditions set by the delivery companies, and they get paid per parcel or per hour. Although couriers appear to be working in their own account in legal terms, they are in fact proper ‘workers.’ The promise of “being their own boss” is another aspect of class alienation. In the owner-driver model, the control mechanism is based on performance: couriers receive performance payments in proportion to the number of parcels they deliver. The more parcels they deliver, the better wages they get. For most couriers, this means skipping meals or other breaks. They just continue delivering parcels while risking their lives in a traffic flow among motorists who are blind to motorcycles and in low-quality outfit and equipment with poor protection. As fast as they can be. And without any security as they don’t have any legal affiliation with the work place whose parcels they deliver.

“WE ARE NOTHING MORE THAN CONSENTING SLAVES”

Many couriers we talk to say the main problem in the owner-driver model is the lack of oversight and job security. Emre, 27, says in the self-employment model, couriers are caught “in the clamp of being a boss”, and believes fast delivery companies have come up with this idea to cut down on labour costs. Emre used to work in the banking sector but had to leave his job at a finance centre due to mobbing and the pandemic. After being tested by unemployment for some time, he had to start working as a courier due to worsening economic crisis, just like many of his colleagues.

Emre first started working as an owner-driver at Trendyol Go, but after complaining about working conditions there, he was blocked from accessing the delivery application and got fired. Although being his own boss seemed like a good idea, being a self-employed courier has been a complete disappointment for him. When we ask Emre about the owner-driver model, he starts describing the working conditions with anger and acquiescence: “We are supposed to be our own bosses, but the company makes all of the decisions, including what kind of a motorcycle you can use or where you can park your vehicle. The couriers carry all the burden but the company makes all decisions. And the couriers are held responsible for even minor problems. When we first started this job, they told us that we would be our own bosses. We believed that but now we are nothing more than consenting slaves.”

Motorcycle couriers went on a strike on January 25 against low wages and poor working conditions

A PERFECT SYSTEM TO AVOID COSTS AND LIABILITIES

The contracts executed between the couriers and fast delivery companies says that “the relationship between the company and the courier is not based on giving orders and instructions, and the couriers are self-employed professionals who have their own tax certificates and who manage their delivery operations independently.” Companies refer to this article to offer justification to their argument that couriers work for their own account. The couriers, however, do not agree and say that it’s quite the opposite in practice.

İbrahim, 34, who is an owner-driver, says the model is a “method to avoid costs and liabilities.” İbrahim used to be an academic but was sacked from his job at a university with a decree law. As he was dismissed with a decree law, he could not find a job and, like Emre, he had to start working as a delivery courier to make ends meet. İbrahim says “Becoming an owner-driver is one of the worst things that has happened to me. In this system, couriers are called bosses but the employers take away all of their earnings.”

“WE ARE NOT BOSSES - THE REAL BOSSES PUT THEIR BURDEN ON US”

Mehmet, who is an owner-driver at Yemeksepeti, has been working in this industry since he was 16 years old. Being a courier has become his profession that he will keep doing until his retirement. He has had so many accidents that there are almost no unharmed bones in his body. Mehmet complains about the recent transformation in the sector and says the owner-driver model is ‘a scam’: “In this sector, all companies are the same. The only difference is the severity of poor working conditions. They say self-employed couriers are ‘boss couriers’ but we are not bosses at all. They first pour honey in your ear and you say ‘Oh, I’m going to be my own boss.’ This is how they scam people. We cannot even choose our shifts. If I cannot go to work one day, they cancel my shifts in the next two days. Just because I didn’t show up. How can they ban a boss from his own company? If I don’t get a doctor’s note, they don’t accept my sick leave. It is not being a boss; it is the real bosses putting their burden on you…”

PRESSURE TO DELIVER FASTER IS THE UNDERLYING REASON FOR CASUALTIES

Yemeksepeti, Trendyol Go and similar online ordering companies use a speed- and performance-based system to sustain value production. This system leads to major accidents and even fatalities among motorcycle couriers and warehouse workers. All couriers we talk to say the same things and emphasize that the delivery service companies force them to make deliveries faster. Couriers say the companies exert pressure on couriers “to be faster” and “encourage them to go faster” as they seek to maximize profits, which is the underlying cause of many accidents.

When we ask “Why do you have to drive fast?”, a courier from Trendyol Go says: “We need to drive fast to make money in the performance-based wage system. We race against time. Sometimes we even drive without putting on our protective gear just to have enough time to make one more delivery.”

Trendyol Go does not have a fixed wage system or fixed working hours. Couriers have to work at least 10 hours per day. The company frequently updates wages and hourly tariffs to ensure maximum performance among couriers and to further slash its labour costs. Couriers initially work on per hour wages, but then they choose to be paid per parcel hoping that they would make more money. In this new tariff, they need to deliver more packages to be paid more: “The updated tariffs benefit Trendyol Go more than they benefit the couriers. The real plan is to encourage couriers to deliver more parcels and do more work. To deliver more parcels, the courier has to do a lot of time-saving. According to the previous tariff, couriers had to deliver orders in 30 minutes, but now, under the new tariff, the delivery time can be as short as 15 minutes. And when the couriers make early deliveries, they get a chance to go back and pick up a new order to be delivered. This also increases the risk of accidents.”

PAYMENT SYSTEM HAS BEEN TURNED INTO AN OVERSIGHT MECHANISM

Murat, 24, who also works for Trendyol Go, says performance-based wage system has been turned into an oversight mechanism against couriers, who are psychologically filled with ambition to make more money. Murat underlines that the couriers even violate traffic rules to make deliveries faster and to get a higher payment. According to Murat, the owner-driver model is a brutal system, which has been designed by delivery companies without considering the well-being of the couriers: “I can imagine what kind of plans were going through the minds of Trendyol Go executives as they adopted these methods. They are creating a more brutal system only to have some leverage against their competitors. They offer faster delivery services as an advantage over their competitors. They force couriers to die in traffic accidents just to make more money and create bigger capital. As they promise higher payment to those who deliver more parcels, couriers play dice with death every day to deliver those orders. Every day we hear another report of a courier crashing against a wall or into a car or motorcycles flipping over. Imagine what kind of a race people are forced into. People risk their lives just to deliver a parcel.”

DIFFERENT COMPANIES, SAME OLD POOR WORKING CONDITIONS

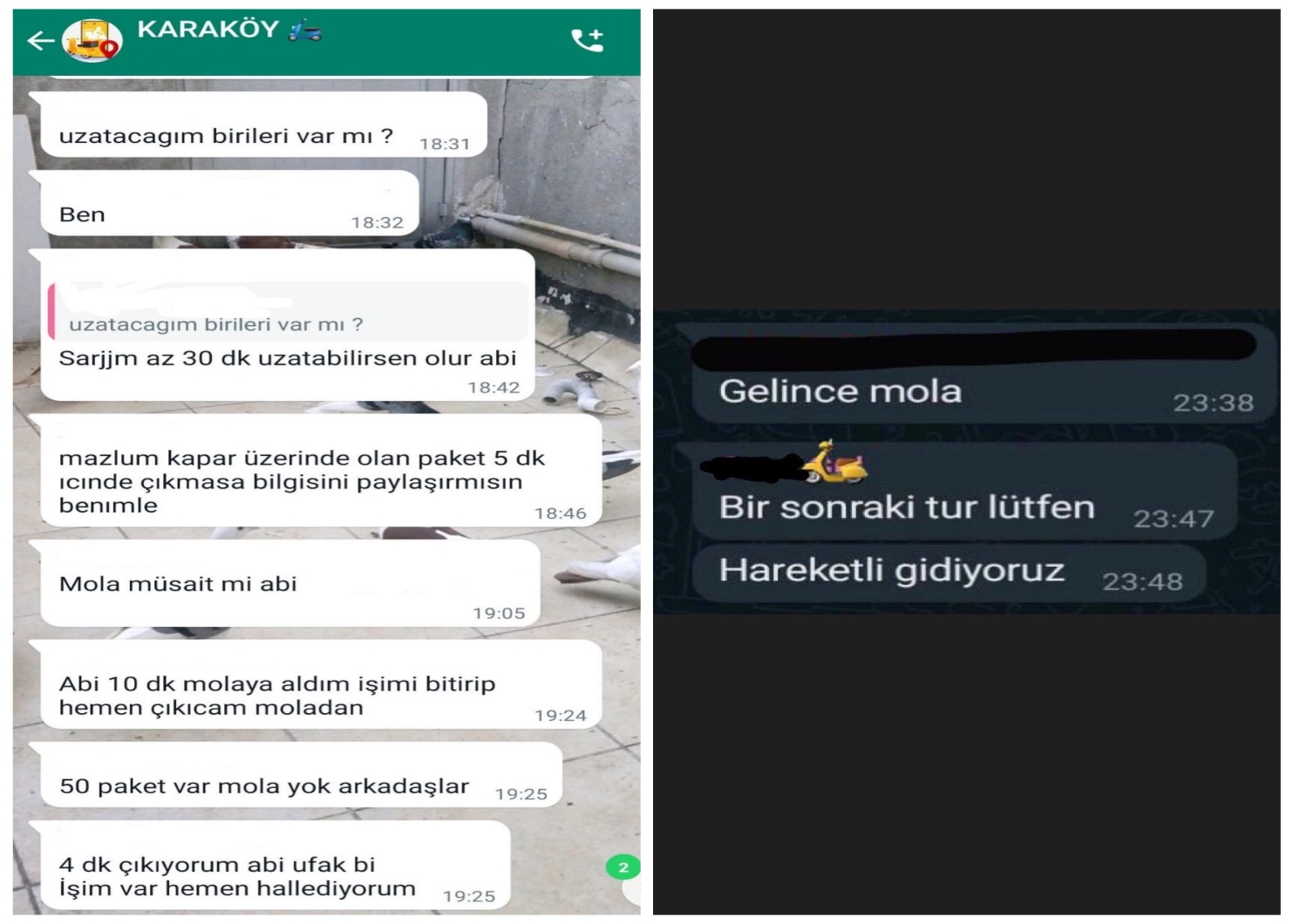

A system that is similar to Trendyol Go is also used by Yemeksepeti, but here the working conditions are poorer. According to the couriers’ account, working hours are arbitrarily extended, and minimum 12-hour working day is mandatory. Otherwise, the company withholds a portion of earned premiums or tips. Similarly, if couriers get sick and take 2 days off, they don’t get any overtime payment. They are under drastic pressure to make deliveries faster, and they are often subjected to mobbing or exiled. Those who complain are fired without a cause.

motokurye 4Weekly working schedule of couriers at Yemeksepeti

motokurye 4Weekly working schedule of couriers at Yemeksepeti

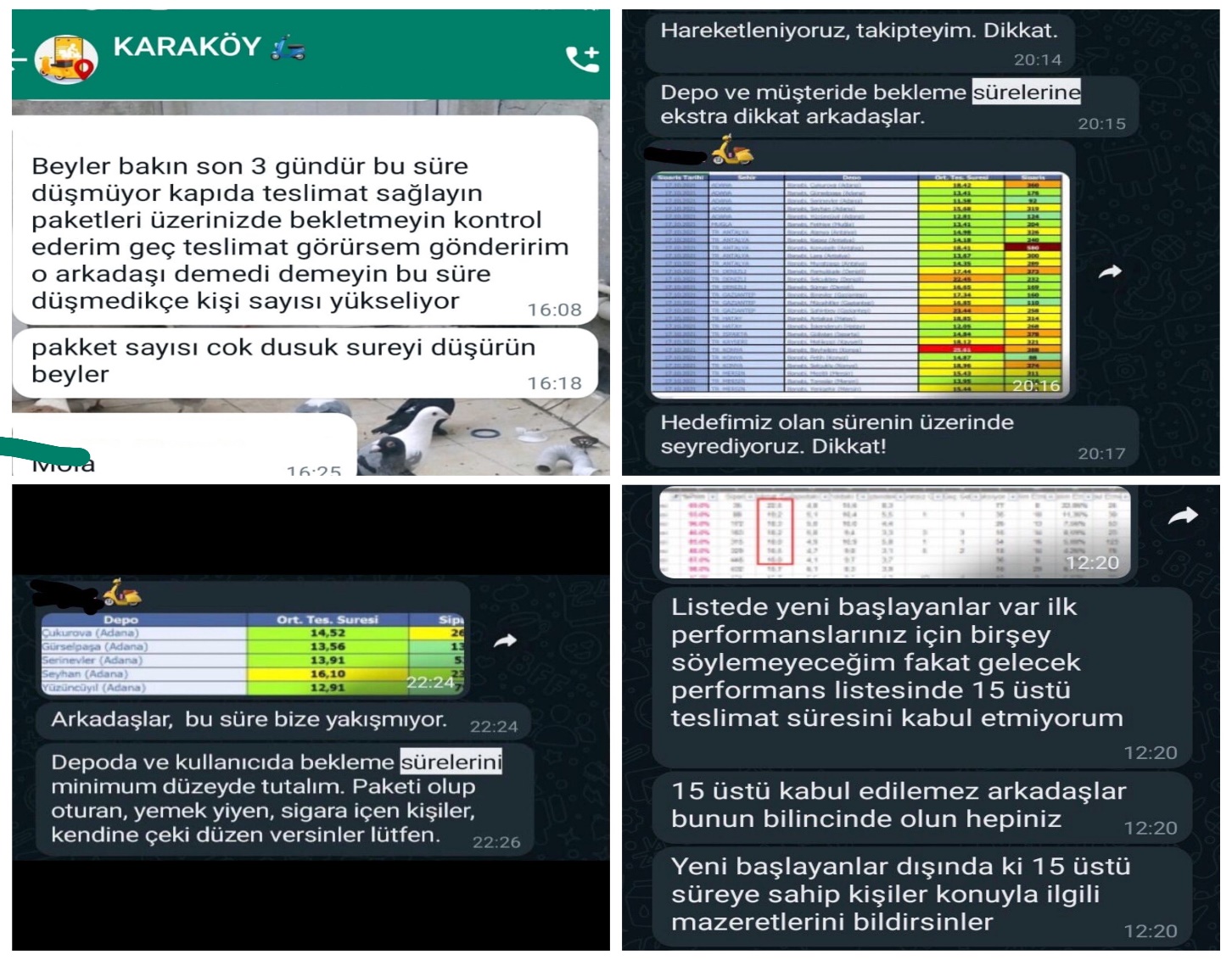

Yemeksepeti oversees the performance of couriers via an application installed on couriers’ smart phones. The application monitors when the couriers pick up parcels, how long it takes them to arrive at the customer’s address, when the delivery is made and how many parcels are delivered. The data collected by the application is compiled in a periodical performance report, which is then used to calculate the fee per parcel to be paid to each courier. However, this fee is essentially based on the green and red codes set by the company. If the performance of a courier is in the red code, it means the courier has delivered orders in longer times than the time specified by the company, which results in cutbacks in wages. If the courier does not improve this performance, they are either exiled to a different area or fired.

motokurye 5Weekly performance charts of couriers

motokurye 5Weekly performance charts of couriers

CONTINUOUS MOBBING ABOUT DELIVERY SPEED

“Performance-based wage system costs our lives” says Ilyas, 24. He explains the mobbing and pressure about delivery speed at Yemeksepeti: “There is just too much pressure about time. At our warehouse, there is a distance limitation of 3 kilometers. After we prepare an order, we are supposed to deliver it in 5 minutes. Otherwise, we are considered as poor performers, and this affects our wages. Supervisors warn us about late deliveries. There is continuous mobbing about this. This time limit has been established without taking other circumstances into consideration. For example, traffic jams or the location of the destination or the number of floors you need to climb to deliver parcels are not considered in this calculation. Therefore, we are forced to violate traffic rules. As a result, we risk our lives.”

motokurye 6Couriers are under continuous pressure to go faster in WhatsApp groups used by Yemeksepeti

motokurye 6Couriers are under continuous pressure to go faster in WhatsApp groups used by Yemeksepeti

75 PERCENT OF COURIERS UNDER PRESSURE ABOUT SPEED

International Labour Organization (ILO) Turkey office published a report on December 10 titled “Focus on Motorcycle Couriers: Psychosocial Risk Analysis in Delivery Sector Employees.” The report emphasizes that the major psychosocial risks affecting couriers include the increasing work burden, increase in working hours and work intensity, and insufficient break times that are disproportionate to the workload. The report reveals that motorcycle couriers suffer from psychological pressure from their supervisors, and 75 percent say they are forced to make deliveries faster.

When asked about working schedules and risks related to shifts, 48.6 percent of couriers complain about the mandatory 12-hour working day. Furthermore, the report underlines the psychosocial risks related to the work environment. According to the report, 84 percent of couriers are faced with difficulties as they have to work even in adverse weather conditions, including heavy rain and extremely high or low temperatures. 77.3 percent say they cannot truly take a rest at break-times as they don’t have a specific area to refresh themselves during breaks.

“WE EVEN SKIP BATHROOM VISITS”

Ferhat, a courier at Yemeksepeti, stresses they cannot even meet their most basic needs since they are under pressure to be faster, and complains about mobbing: “If I had another option, I wouldn’t be here and I wouldn’t do this job. We don’t have fixed working hours or weekly or annual holidays. We work 11 or 12 hours per day, sometimes we even do 15-hour shifts. We cannot even see our family. For what? To make a few pennies more and make a living. Despite this heavy workload, we are under constant pressure to make deliveries faster. Sometimes we have to take a bite on the motorcycle as we ride to deliver a parcel. On some days we are so busy that we even skip bathroom visits. Once I desperately had to go, so I just stopped the motorcycle and relieved myself in a hidden spot on the roadside.”

motokurye 7On busy days, couriers are forced to delay their break times or not permitted to take a break at all. Sometimes couriers even have to skip bathroom visits.

motokurye 7On busy days, couriers are forced to delay their break times or not permitted to take a break at all. Sometimes couriers even have to skip bathroom visits.

MAXIMUM DAILY DRIVING TIME SHOULD NOT BE MORE THAN 8 HOURS

Tuğrul Katkak, a safe driving trainer at TURING, says long working days for couriers mean higher risk of accidents. According to Katkak, the maximum daily driving time should not be more than 8 hours. Besides, taking a break every 45 minutes should be mandatory. Katkak says couriers are excessively tired: “If a person spends 5-6 days of the week on a motorcycle without resting, that person will feel more tired than someone who rides a motorcycle once a week. Being more tired means higher risk of accidents.”

HOW MUCH DO MOTORCYCLE COURIERS MAKE?

Although there is an overall perception that couriers make good money, in fact their wages are not high enough to justify their poor working conditions. Another striking point in the ILO research is the mismatch between the working conditions of couriers and the renumeration they get. According to the research, the average monthly income of a courier is around 5,117 TRY ($345).

The couriers whom we interviewed for this report confirm the figures given in the ILO report. They receive approximately 10% commission over the price of each parcel they deliver. Some couriers make 6,000 while others make 7,000 or 8,000 TRY per month, depending on their performance. However, they all agree that being an owner-driver means a huge burden of costs for couriers.

Hikmet makes 8,000 TRY per month, but after expenses and taxes, what remains is barely higher than the minimum wage: “If you subtract your daily costs, including gas, insurance premiums, bookkeeping fees, taxes and vehicle repairs, you are left with almost nothing even if you make 10,000 liras per month. Imagine that you need money, and you work from 9 am to midnight, risking your life and without seeing your friends and family, and you get almost nothing in return. So, in exchange for risking your life for 12 hours, all you get is misery.”

motokurye 8Numbers of packages delivered by the same courier on two different days

motokurye 8Numbers of packages delivered by the same courier on two different days

IS BEING AN OWNER-DRIVER A PRECARIOUS LINE OF WORK?

Indefinite-term employment contracts between couriers working in the traditional fast delivery sector and companies are rather common. With these contracts, couriers have job security and can go to court if they become victims of unfair or illegal conduct. The rights of the workers specified in the Labour Code include renumeration, overtime payment, resting time, annual leave, and being protected and respected by employers, and prohibition of forced labour. The employers have to pay social security premiums for workers so that they can have insurance coverage against short- and long-term risks. However, in the owner-driver model, companies can easily relieve themselves of all liabilities related to the couriers.

Owner-drivers work in their own account, and therefore they are not protected by the Law no. 6331 on Occupational Health and Safety. In terms of social security, they are considered in the same category as other self-employed professionals according to article 4/1-b of the Social Security and General Health Insurance Law no 5510, which describes the insurance coverage offered to self-employed professional groups. As owner-drivers are legally considered as self-employed professionals, they cannot enjoy the benefits offered to workers against social risks.

Above anything else, access to their right to healthcare is a major problem. Individuals who are employed as workers can unconditionally benefit from the coverage offered under the General Health Insurance; however, couriers are categorized under article 4/1-b and therefore they can access healthcare services under the General Health Insurance system only if they have paid all of their insurance premiums. According to a study conducted by Erkan Kıdak in 2021, the majority of couriers do not have access to healthcare services due to unpaid premiums.

Being categorized as a self-employed professional instead of a worker has an adverse impact on working conditions of couriers. In addition to lack of access to healthcare, they do not enjoy any other benefits such as overtime payment, right to rest, weekly off-days or overtime payment for work done on national holidays: “There are many disadvantages of being an owner-driver. For example, we don’t have Social Security Insurance coverage, private insurance, compensation for exhaustion, annual leaves, paid meals, or payment for vehicle costs, outfit costs or gas costs. If we have an accident, the company will not have any liabilities. For example, I had an accident and they put my leg in a plaster cast. I had to pay all costs myself even during the time when I was not able to work.”

* This article has been prepared in the scope of the “New Generation of Investigative Journalism Training Project” which is implemented by Media Research Association in cooperation with ICFJ (International Centre for Journalists).

** The names of the couriers and the dates of events they describe have been changed.

trendyol-1

trendyol-1