Written by: FAZIL ALP AKİŞ

Translation: Sebla Küçük

We meet with T. Cengiz on a Friday evening at a hookah lounge in Ümraniye district in Istanbul. Another treasure hunter, F. Yunus*, who convinced Cengiz to talk with me, meets me at the entrance of the venue and tells me that I should listen to Cengiz very carefully. Cengiz is in his 50s, but somehow looks older. He has a stubbly face, and holds a cigarette between his lips, which will be replaced by many others in the next few hours. During our three-hour conversation, he tells me how he got into treasure hunting and artefact trafficking business, significant trafficking cases he witnessed, the major players in the trafficking sector in Turkey, and “the mythology of gold” from the eyers of a treasure hunter.

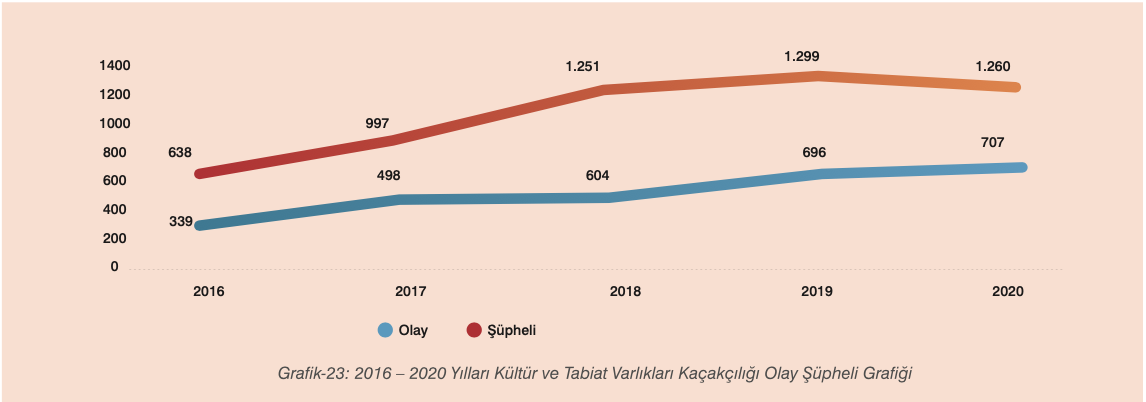

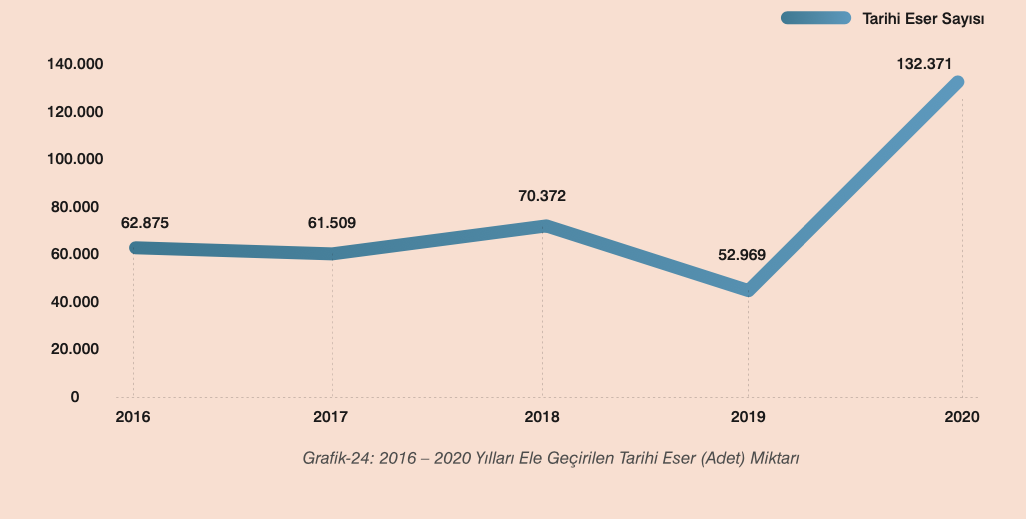

About four months before our meeting with Cengiz, I started doing some research on trafficking of historical relics in Turkey. According to a 2020 report by Department of Anti-Smuggling and Organized Crime (KOM) at the General Directorate of Security (EGM), there were 707 raids against trafficking of cultural and natural assets in that year. 1,260 suspects were investigated and 132,371 historical artifacts were seized. The number of trafficking cases and the suspects has gone up by 100 percent since 2016. It was also in 2020 when officials seized 66,781 historical relics in a single raid, breaking a record.

Source: 2020 Report by Department of Anti-Smuggling and Organized Crime

Source: 2020 Report by Department of Anti-Smuggling and Organized Crime

Source: 2020 Report by Department of Anti-Smuggling and Organized Crime

Source: 2020 Report by Department of Anti-Smuggling and Organized Crime

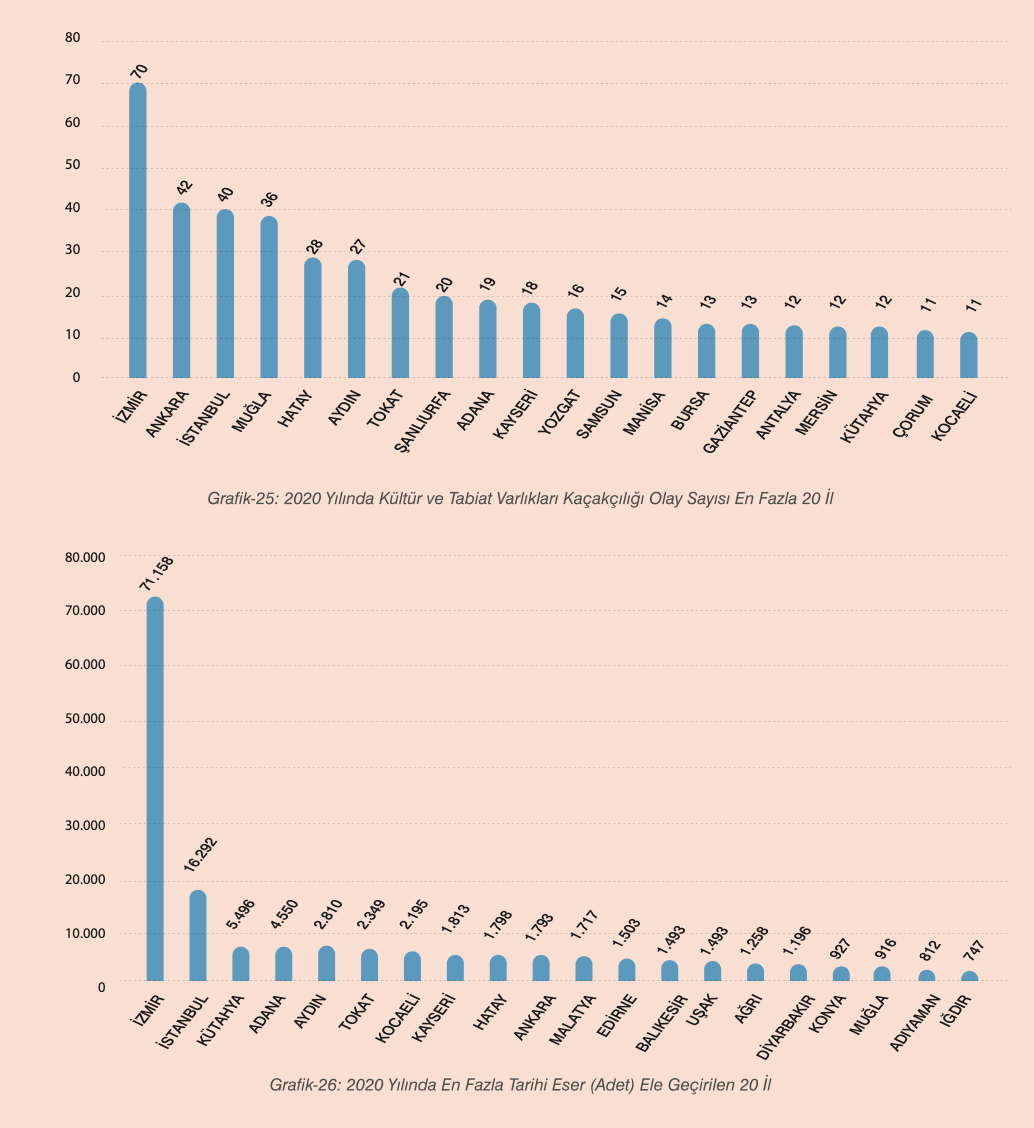

The report lists the Turkish provinces where most trafficking incidents occurred throughout the year. These provinces mainly include metropolises, port cities where artifacts can be passed through customs more easily, cities with historical sites and their surrounding areas, and cities with high number of collectors and antique dealers with criminal records.

Source: 2020 Report by Department of Anti-Smuggling and Organized Crime

Source: 2020 Report by Department of Anti-Smuggling and Organized Crime

SMUGGLING BEGINS WITH TREASURE HUNTING

KOM describes the method used by traffickers of historical relics as follows: “Traffickers want to take cultural artifacts abroad. To do this, the relics found by ‘thieves/hatchet men/illegal diggers’ are not handed over to museums within the legally required time period; instead, they are sold to collectors and antique dealers at higher prices.”

Illegal trading of cultural property is one of the top agenda items in Turkey with numerous reports of artifacts stolen from museums, sting operations on traffickers or news about treasure hunters. Archeologists tell me that it is true that artifacts are sometimes stolen from museums or excavation sites; however, the illegal journey of artifacts often starts with a treasure hunter. Sam Hardy, a researcher on cultural property crimes at Oslo University, Norwegian Institute in Rome, argues that most treasure hunters can do this only because they are “protected.” Hardy says, “Quite often, treasure hunters have some kind of protection. And this is not only the case in Turkey – all around the world it’s the same. In most of the cases, the ones protecting treasure hunters are low-rank, corrupt civil servants. However, like arms dealers or drug smugglers, there are also treasure hunters who are under the protection of senior officials.”

Zafer Akkuş and Tamer Efe, two scholars who talked to an expert about trafficking when working on their academic paper titled “Combating Trafficking in Cultural Property by the Police in Turkey”, say, “When we look at the overall characteristics and structure of criminal organizations involved in trafficking of cultural property, we see that there is a hierarchy among the members. They often try to build contacts with public officials, and plan ahead for their criminal activities. They have international ties and contact with the rich, particularly with Turkish or foreign individuals who are interested in history or arts. These people have criminal records, and their conversations are short and often encrypted. I believe there is an upward trend in trafficking of cultural property across Turkey.”

Official and academic sources demonstrate the scale and numbers in trafficking of historical artifacts. I talked to archeologists and museologists to understand how relics that are buried underground end up in collectors’ living rooms or auction houses in Europe. Before long, I realized that I was not going to have a genuine insight of the business without listening to first-hand witnesses, i.e., traffickers and treasure hunters. After a long search, I met with Yunus who gave me a striking account of what was happening in the world of trafficking. In his own words, Yunus was actually hunting treasure “as a hobby.” During our conversation, he realized my questions could only be answered by an expert, and agreed to introduce me to Cengiz, who has far more experience and is considered to be “one of the best.”

FIRST TREASURE DISCOVERY AT CHILDHOOD HOME

Cengiz was born in a village in İliç district of Erzincan, in east Turkey. He spent his childhood years in Istanbul, mostly near Taksim area. He tells me that he was a notorious bully when he was young, and his career as a treasure hunter started after he beat the son of the Chief of Police of Istanbul. After the incident, his family was afraid that he would be killed in retaliation, and so they left their home in Taksim, which they had bought from a priest many years ago, and sold it to another family from Erzincan. After they moved out, Cengiz heard rumors that there was some gold buried somewhere in the house. He convinced the new owners and searched the building with metal detectors with the help of a relative. The duo found some clues showing there could be gold in two locations, but the new owner didn’t let them dig it out. As he takes a puff from his cigarette, Cengiz says, “The new owners dug out the treasure in one of those two locations and they became rich. Now they live in a different place, but they won’t even rent out this house. I still want to go there.”

Cengiz’s hometown, İliç district in Erzincan

Cengiz’s hometown, İliç district in Erzincan

After this experience, Cengiz’s path crossed with other treasures buried underground but he couldn’t get any share from them. He surveyed the ground under his aunt’s house in Taksim, and identified the location of the gold, but his aunt didn’t let him dig it out. Cengiz says she later became very rich, implying that she dug out the gold herself. He also found a tunnel beneath the house of his mother’s milk-sister, but the owner blocked the tunnel with concrete.

In his 30-year career as a treasure hunter, Cengiz came within a whisker of finding a treasure several times, but he could never make good money out of this business: “I was famous – people would call me from all around Turkey. We often made good guesses about the location of treasures, but we did not make any money. I believe I will go to heaven because I’ve been scammed a lot.” According to Cengiz, treasure hunting is a “patriotic” act, and not something illegal: “I can’t get myself into trouble because I’m not doing anything illegal. You become a criminal if you dig it out, but you’re good if you’re just looking for it.”

HOW DOES THE TRAFFICKING SCHEME WORK?

I ask Cengiz how historical artifacts are unearthed and sent to buyers. The journey often starts with a shepherd or a peasant walking around a village and coming across a sign. What treasure hunters call a “sign” is actually a scene or an object which strikes the eye and doesn’t look natural. A hole in a mountain, rocks standing in a symmetrical order, animal-like symbols or inscriptions on rocks… When a person comes across these signs, they tell it to a relative or friend who is interested in treasure-hunting. They find someone who has good knowledge about treasures via networks of family or people from the same hometown. This is when Cengiz steps in: “They finally come to me. If I tell them where the treasure is and if they find it there and dig it out, they have to give me a finder’s fee unless they are too greedy.”

So Cengiz and others like him are consultants in treasure-hunting. Consultants visit sites, read the signs and make recommendations to those who want to put their hands on the treasure.

The paper titled “Combating Trafficking in Cultural Property by the Police in Turkey” by Akkuş and Efe describes the subsequent phases of trafficking scheme: “When we look at the criminal profile of traffickers of cultural property, we see that these artifacts are illegally dug out from mounds, historical ruins or tumuli, and brought to big cities by gatherers. Then, they are sold to auction houses, galleries or collectors abroad by dealers, and transported by shipping companies. It has been revealed in the research by the police department that ‘dealers’ who trade cultural property abroad have trafficked relics from Anatolia which were later put on sale at galleries and auctions.”

HOW IS A TREASURE UNCOVERED?

According to Turkish Directive on Treasure Seeking, illegal treasure-hunting is a criminal act. Those who intend to search for a treasure are required to submit a detailed letter to the authorities and undertake an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). Cengiz says the legislation doesn’t create an unsurmountable barrier for treasure-hunters: “I will dig it out if I want to. How? I can say ‘I will plant walnut trees’, and the Provincial Directorate of Agriculture will give me the necessary permit. Or I can say ‘I will build a water reserve’, or ‘I will make it a picnic area because we have guests coming to the village.’ You must play it by the book. If you plant walnut trees, they will pay you some incentive. If authorities ask about them, you can say ‘Walnut trees just died’ when you’re done with excavating the area. There will be no penalty for that.”

A site dug out by treasure hunters with excavators in Torbalı, Izmir in 2015

A site dug out by treasure hunters with excavators in Torbalı, Izmir in 2015

An illegal, 25-meter-deep excavation site in Avcılar, Istanbul in 2021

An illegal, 25-meter-deep excavation site in Avcılar, Istanbul in 2021

There are, however, unwritten rules for treasure hunters: “You can only dig an area in your own village. You can’t go to another village and just start digging. You will get beaten.” Cengiz says hunters can do small excavations illegally without filing an official application, but still, the police and gendarme pose a significant risk for them: “If the police catch you on the job, they report it and seize your goods. If traffickers run away, the police destroy the report and keep the goods for themselves.”

Cengiz gives an account of how unearthed gold and artefacts are delivered to buyers: “Avni Seyir*, who was a guard at Mecidiyeköy branch of a bank, contacted us via an intermediary. We went to Tekirdag with him. A man from his village told Avni about me, and so he found me. We went to the village… We looked at the signs and used a metal detector, and we finally found the gold in the middle of the bridge. Avni didn’t let us dig it out. 10 days later, he sent me some samples, saying ‘My friends dug the gold out.’ He wrote there were 1200 gold coins and around 14,000 silver coins. I took the samples to a store in Fatih. The owner offered me $300 per silver coin and $2,600 per gold coin. We could have made $8 million for all of it. We would give $6 million to Avni, and keep $2 million for ourselves. But Mehmet got greedy, and offered only $200,000 to him. It didn’t work.”

An excavation by treasure hunters under a Roman stone bridge located 3 km west of Iznik, 2018

An excavation by treasure hunters under a Roman stone bridge located 3 km west of Iznik, 2018

Excavations by treasure hunters near the abutment of a 73-year-old bridge in Yunus Emre district of Manisa, 2021

Excavations by treasure hunters near the abutment of a 73-year-old bridge in Yunus Emre district of Manisa, 2021

DANGERS OF TREASURE-HUNTING

As I listened to the stories of treasure hunters, I noticed an interesting pattern: the biggest problems emerge after the treasure is found. Treasure consultants like Cengiz get scammed after they help others locate a cache, or diggers get into a fight among themselves. However, to keep their business up and running in the long term, treasure consultants bear those risks and don’t chase commissions. Thus, they witness many people becoming rich after finding a treasure as well as others getting caught or harmed by their luck, and yet, as consultants, they can continue doing their job.

Greed is another danger that threatens illegal diggers. Cengiz says he has heard dozens of stories in which people pull a trick on each other, or even kill each other right after working together to dig the treasure out. Once, he was also involved in a similar incident. He and an intermediary went to İnebolu district in Kastamonu with a team of 10-12 people. They were contacted by three brothers who wanted to find the treasure. They located some gold, and suspected that there could be more of it. As they kept digging to find the treasure, Çetin found a belt buckle and put it in his pocket. Then they found “the actual thing” but they didn’t dig out the treasure. I ask him why. He says, “If we dig it out, there would be chaos and they would start fighting each other. There are many stories like this.”

There are also other threats that treasure hunters fear: genies. Many diggers, particularly those planning to search areas near old graveyards, bring with them spiritualists who recite prayers for protection against genies. According to treasure hunters I talked to, there are two main reasons for this belief: the first reason is the treasure hunters who want to keep their find as a secret. When they come across a very big fortune which is too heavy to carry at once, they tell horror stories about the area to keep others away. Some use this method even if they can’t find any treasure in an area. “People think we are the second-best liars after game hunters. If a treasure hunter fails to locate the treasure, he will say ‘genies moved it to somewhere else’ to save face,” Cengiz says.

Introduction of an article on the relationship between genies and treasures on a blog about treasure-hunting

Introduction of an article on the relationship between genies and treasures on a blog about treasure-hunting

Another reason that makes genie stories popular is the toxic gases in old graves, wells or closed chambers. These gases, after being trapped in cave-like spaces or released by decaying organic materials, can pose a fatal risk for amateur diggers. As people hear reports of treasure hunters who die during excavation works, they believe that these areas are protected by genies.

WHO ARE THE BUYERS?

After managing to locate, dig out and unearth a fortune, diggers have to overcome the biggest challenge: finding dealers. It can be argued that, in trafficking of cultural property, buyers are in a better position than dealers. According to Cengiz, gold is the best fortune for a treasure hunter because it’s expensive and can be melted and sold, without leaving a trace. Cengiz says this method is becoming more and more popular: “For the last 4-5 years, those who find some gold or silver have been melting it. Some don’t prefer this. There are some dealers in Gaziantep and at the Grand Bazaar who do this.”

Beginners in treasure hunting or those who come across historical artifacts by chance first go to online platforms to sell their find. In a few minutes, you can find numerous Facebook groups on treasure hunting, and get some idea about how to sell artifacts in forums.

However, Cengiz says there are many undercover police officers on these platforms who pretend to be buyers or dealers. Cengiz, who also sells altered second-hand cars, says a talented dealer like himself can copy any feature in a car. Dealers like Cengiz, who are called “spot dealers”, buy good-looking old cars and fit them with old engine parts, and sell them at very high prices. With this analogy, Cengiz implies that many artifacts sold online may be fake but he doesn’t reveal if he’s involved in sales of fake artifacts. According to him, for someone who wants to sell some artifacts, the only hope is finding a reliable intermediary: “If you don’t work with people like me, you can’t sell your goods. Those people on the internet are all cops.”

A few examples of the Facebook groups where treasure hunters meet

A few examples of the Facebook groups where treasure hunters meet

SALES OF ARTEFACTS VIA SOCIAL MEDIA REPORTED BY DEPARTMENT OF ORGANIZED CRIME

The 2020 report by KOM reveals that archeological forgery has been on the rise in recent years. The report says antiquities traffickers also use the internet and social media for their business: “There are numerous images of illegal excavations and historical artifacts on e-commerce websites and social media platforms. Individuals who find antiquities by coincidence when walking around rural areas or plowing their land post images of these artifacts in groups on social media and try to get information about its origins and potential price. When they find buyers, they contact them by direct message.”

According to Cengiz, buyers include “prominent families in Turkey.” Reminding that these families have rich collections including many illegal historical artifacts, Cengiz says he also sold some goods to one of these families – they often use their employees, such their facility managers, as intermediaries in these deals. Some of these families also scam treasure hunters. For example, a treasure hunter contacts the family and sends a small sample of the treasure and receives a generous payment for it. Then they make a deal for the whole fortune and meet at a villa. However, treasure hunters are welcome by armed guards, who seize their goods without any payment. Treasure hunters later go back to the same villa with a group of armed men, only to find that the place is for rent and no one lives there.

As the whole deal is illegal, scammed sellers can’t go to the authorities. So, in the unreliable world of treasure-hunting, “the stronger one” can beat the others when digging out a fortune or when selling it. The buyers who are economically stronger are the ones who profit from this exchange.

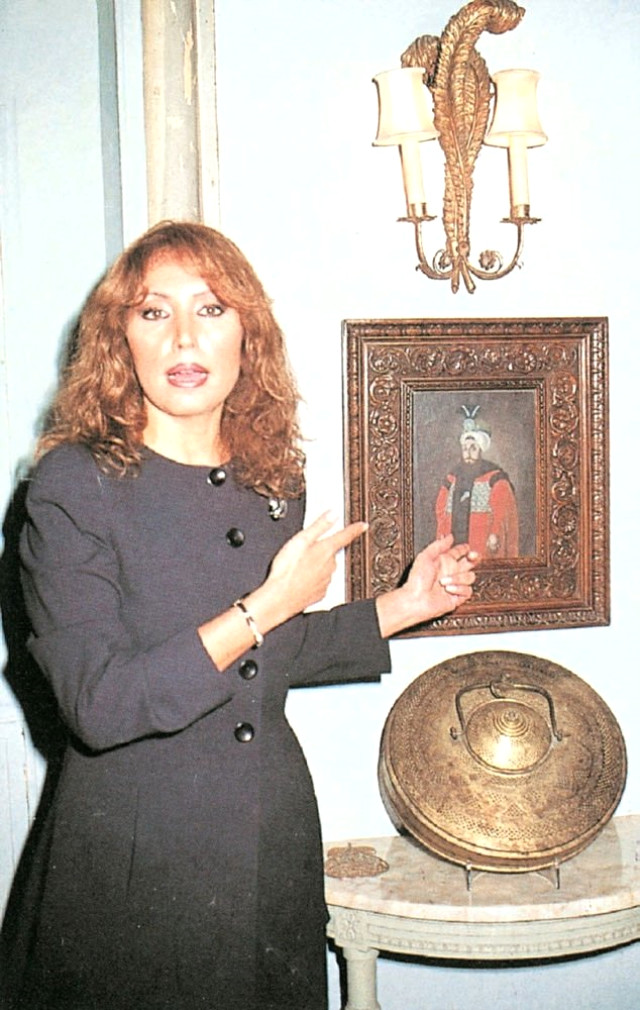

Ayşegül Nadir (Tercimer)

Ayşegül Nadir (Tercimer)

According to Cengiz, these rich families play an important role in antiquities trafficking, who sometimes smuggle artifacts on their private boats or yachts. “I even know the location of their stash on their boat,” he says. He adds Ayşegül Nadir (Tercimer) is also a well-known figure in this market. “She ran away. She is a brave woman,” he says.

BUYERS ACT UNDER IMPUNITY

Archeologist Dr. Elif Koparal says holding companies and rich collectors comprise the backbone of the antiquities trafficking market: “Treasure hunters are a big problem but the actual problem is the network of big companies who drive this business. There are some artifacts of unknown origins at well-known museums, which encourages treasure hunting and trafficking. There are artifacts on London’s streets which actually belong in museums. Treasure hunters sell their find to rich people whose names we all know.”

The authorities are also aware of the role of collectors in antiquities trafficking; however, they say “gaps in the legislation” are the real problems: “We have revealed that some collectors operate legally but they are also involved in antiquities trafficking by using gaps in the legislation. In this context, if they are caught when selling antiquities, they say they recently acquired the artifact and they are going to have it registered. So, they can get away without any penalty, and keep doing the same thing.” Thus, it can be argued that treasure hunters and intermediaries take significant risks with potential legal consequences but for the actual buyers getting caught is not a big problem.

TREASURE HUNTING AND THE BIGGER PICTURE

What is just as interesting as Cengiz’s testimony about antiquities trafficking and treasure hunting is his perspective and worldview. Cengiz describes himself as “an avid follower of Ak Party.” He constantly insists on his claim that the amount of unearthed gold in Turkey is “beyond our imagination.” Cengiz says he wants to volunteer to find all of that gold: “If the state gives me the permission, I can pay all of their 450-billion debt. I can sign a bill for this.”

Furthermore, according to Cengiz, the state has been involved in some treasure-hunting operations in recent years, and therefore it’s trying to prevent treasure hunters: “Erdoğan did his best to prevent treasure hunters. He introduced new legislation. If he makes this business legal, he will get 5 million votes because we are 5 million people. In the past, we had people protecting us, and we could get away even if we got caught. But now there’s no one to protect us. The state is also doing this business. Berat Albayrak flew over the whole country on a helicopter, and he knows the locations of treasures. This is why Erdoğan isn’t worried about the economy. The money goes to the vault of the state, not into people’s pockets. They can’t do this via official means. If they try to dig out artifacts and sell them by legal means, all of the money would go to the Greeks.”

According to Cengiz, political issues are intertwined with the hunt for gold. The ‘Istanbul Canal’ project is one of these issues. Cengiz says large amount of gold is buried in the areas where the Canal will be built, and this is why President Erdoğan insists on the project: “Erdoğan once mentioned the gold stashed in Çatalca. 12 ships that belonged to the Knights Templar are buried there with 300 tons of gold. Erdoğan said ‘You want to have the Genoese ships but I’m not giving them away.’” I couldn’t find these remarks in archives but Assoc. Prof. Kağan Kurtoğlu mentioned a similar story at a news program on A News, a pro-government television channel: “Beneath the Istanbul Canal, there are 10 ships filled with gold that belonged to the Templars. Mr. President knows about them.”

At this point in our conversation, Cengiz starts talking about this story, which, he says, is “the most important story in the world of treasure-hunting.” According to rumors, the Knights Templar, with the aim of ending the Ottoman Empire, went to several Anatolian villages and slaughtered all peasants except for a few children. The knights trained those children to operate as spies against the Ottomans. When these children grew up, “They worked with grand-viziers, who were converted Christians, and robbed the caravans carrying gold that was collected as tax, and they buried these gold coins in the ground. This is how the Ottomans lost its gold and went bankrupt.” Cengiz says, this gold is the big stash that all hunters are looking for: “There are three types of treasures. The first is the treasure buried by robbers – the treasure hunters looking for a big find search for this kind of treasure. The second is the gold left behind by Armenians who migrated. And the third is the treasure buried in tumuli or graves. Hunters look for smaller fortunes to learn the job, but their actual goal is to find the big treasure. You can see signs around big treasures, but there will not be any signs for the gold left behind by Armenians.”

Two Lydian tumuli in the 2,700-year-old site in Bintepeler in Ahmetli, Manisa were dug open with excavators by treasure hunters, 2021

Two Lydian tumuli in the 2,700-year-old site in Bintepeler in Ahmetli, Manisa were dug open with excavators by treasure hunters, 2021

Stories about members of minority groups stealing and hiding Ottoman gold mean that the gold left behind by minorities who fled massacres is “halal” (or legitimate) for treasure hunters. Cengiz believes these gold coins are “treasures stolen from our grandfathers”, and he doesn’t feel guilty about digging out and selling them. To the contrary, he describes himself as a patriot: “These people caused the demise of my grandfathers’ empire. This is a fight for rebuilding an empire. This is not about money! If I found two billion dollars, should I keep it or give it to the state? Well, we search and find it – we are treasure hunters. But that find would belong to the state. Money isn’t everything.”

“80 PERCENT OF EXHIBITS IN MUSEUMS IS FAKE”

Cengiz says that the treasure hunting and antiquities trafficking business was controlled by followers of Fethullah Gulen a few years ago: “Back then, archeologists and managers of museums were involved in this business. 80 percent of all exhibits in museums are fake. They find gold during archeological excavations, but they don’t report it. They always find pots. But was that pot empty? Have you ever seen a pot that is not broken? All of them are broken.”

Cengiz says that not all treasure hunters are patriots like him, and that 90 percent of the hunters do this business out of greed: “The story begins with greed and then turns into pleasure. Imaging walking into a cave that is 3,000 or 4,000 years old. We can touch history. This is an exciting job but those who do it are starving. If God allows, they can make some money of it. We couldn’t make any money – maybe we were not meant to…”

As I pack up my things to leave, I see Yunus showing Cengiz a picture of a rock in his phone. There is a figure carved into the rock, and Yunus says it looks like a rooster. Before sharing his interpretation of the sign, Cengiz gives me a look and says to Yunus, “We’ll talk about it later.”

* The names marked with ‘*’ have been changed for anonymity.

** We contacted the Ministry of Culture and Tourism by e-mail on August 20, 2021 and January 10, 2022 to reach the Department of Anti-Smuggling about the allegations in this article, but our questions were not answered.

*** This article has been prepared in the scope of the “New Generation of Investigative Journalism Training Project” which is implemented by Media Research Association in cooperation with ICFJ (International Centre for Journalists).