Written by: HACI BİŞKİN

Translation: SEBLA KÜÇÜK

Six years have passed since the Emergency Decree Laws which were published in the aftermath of the attempted coup on July 15. During this time, 125,678 people were expelled from civil service under Decree Laws (which are also known as ‘KHK’ in Turkey). Thousands of people, who were dismissed from their civil service jobs as a teacher, police officer, prosecutor, judge, etc., are still employed after six years, and are marginalized by the society.

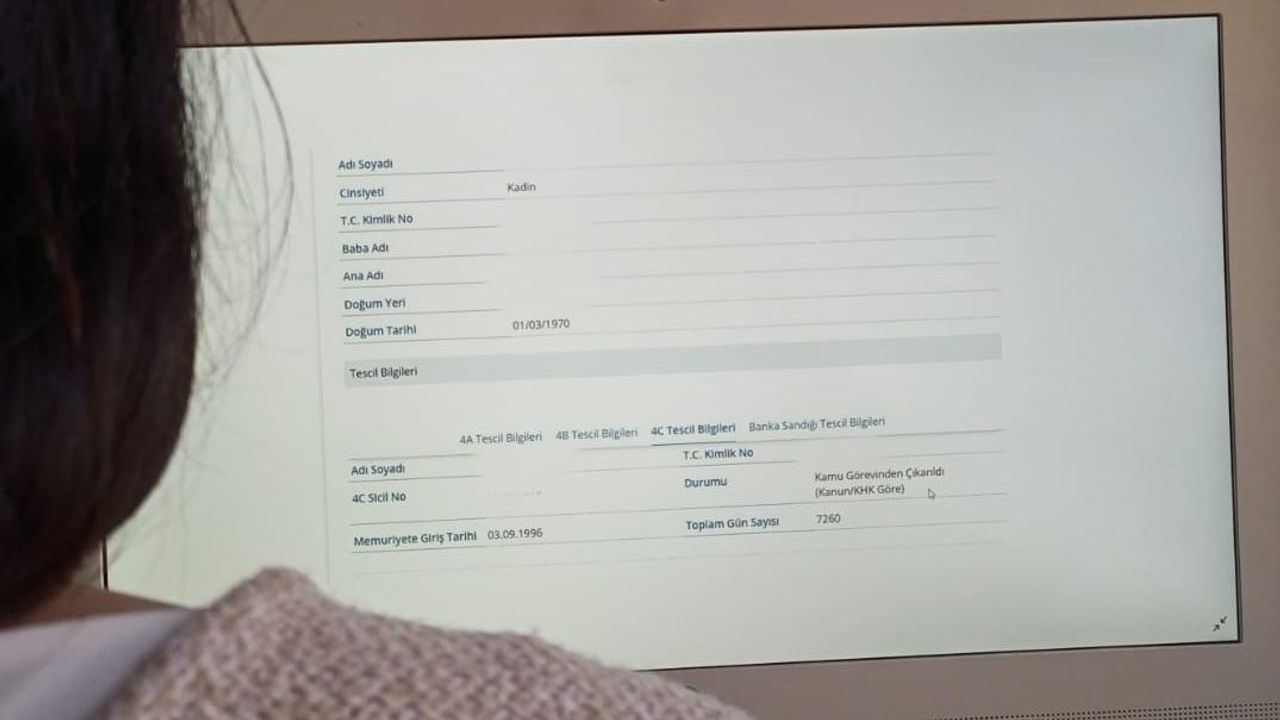

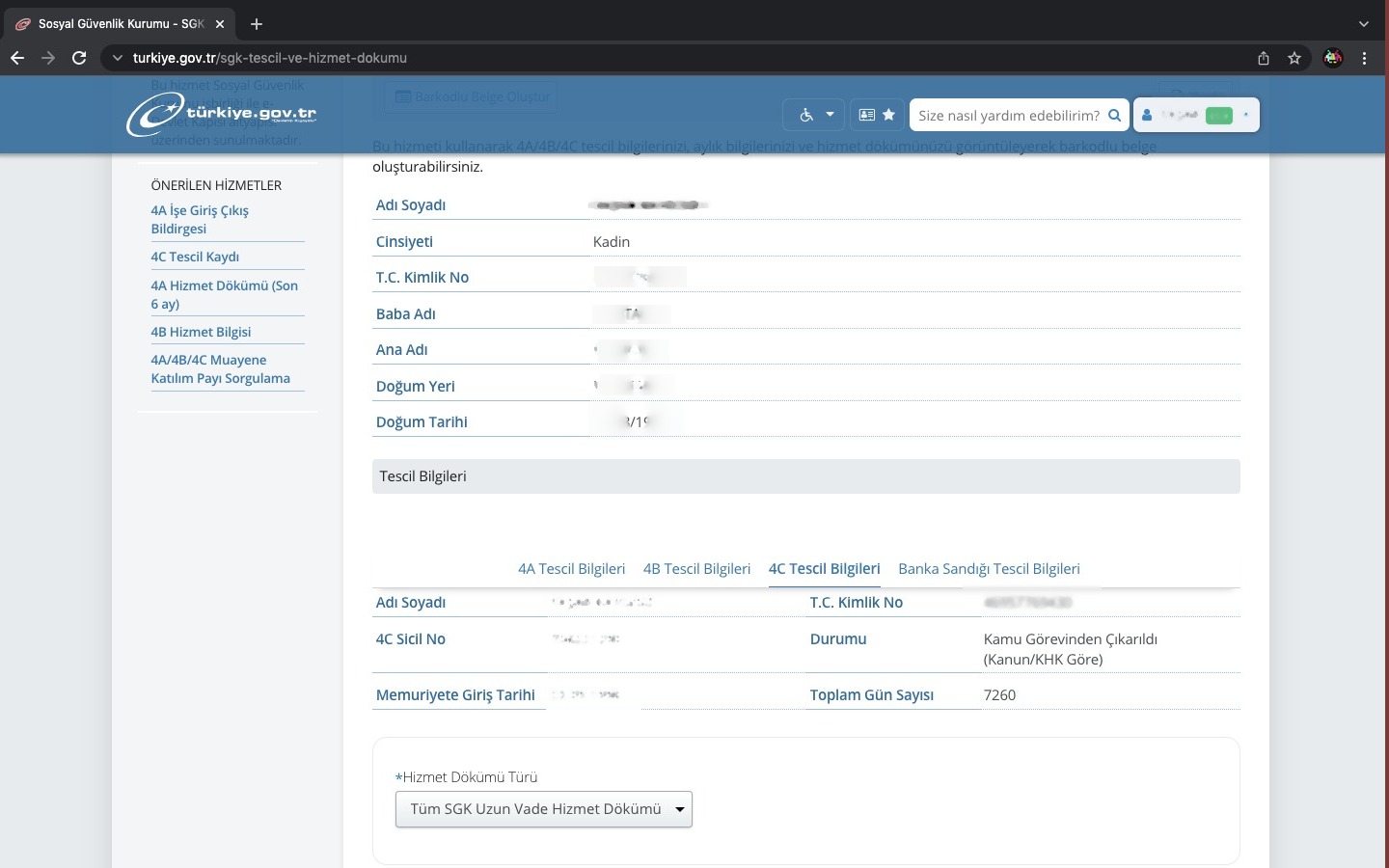

Code 37 is a tag created by the Social Security Institution (SSI) to identify the former civil servants who have been dismissed from office via Decree Laws. 125,000 people who have been dismissed from civil service via Decree Laws know the meaning of this number very well. For them, ‘37’ means disappointment at the end of every job interview.

Employers are aware that this tag shown on the SSI page of the applicant, which indicates that the person has been ‘dismissed from civil service via a Decree Law’, essentially says one thing: “This person is not considered to be a reputable person by the state. Are you sure you want to recruit this person?” There is no legal restriction against hiring someone who has been dismissed from civil service under code 37. However, employers often turn away when they see the letters “KHK” in the SSI records when checking the background information of an applicant. They do not offer any written notification to explain why they decided not to hire that person at the final stage of the hiring process. In most cases, their answer is “Please wait for our response” or “We cannot hire you because you were dismissed from civil service.” Private companies as well as private educational institutions operating under ministries adopt a similar policy.

This policy means a death sentence for former civil servants who were dismissed via Decree Laws. Our investigation looks at the experiences of victims of Decree Laws, whose right to work is violated and who are marginalized. We also analyse the decisions passed by relevant ministries, and try to reveal why private companies avoid hiring people dismissed from civil service via Decree Laws.

WHEN RECRUITERS SEE CODE 37

Mesut was dismissed from civil service on September 1, 2016 via Decree Law no. 672. Soon after that, he realized it would not be easy to find a job in private sector. At the end, he gave up applying for suitable positions and started sending out his resumé for all job ads in Mersin.

His search continued for months; however, nobody wanted to hire someone dismissed from civil service via a Decree Law. Finally, he received a positive response to his application to work in the shipping department at Trendyol, an online ordering company, and he was called in for a job interview, which went rather well.

To execute an employment contract, the employer asked Mesut for his national identification number. Before signing papers, the recruiter wanted to find out why Mesut quitted his former job, and saw code 37 on his SSI page, after which Mesut was sent off with the words “We will call you.”

Mesut describes what happened during the interview: “After the job interview, they wanted to hire me right away. They were going to register me as a new recruit on the SSI system, but then the recruiter asked me ‘Were you dismissed from civil service via a Decree Law?’ They said, according to the official procedures of the company, they had to ask! They decided not to hire me because of that. I told them it was an act of discrimination and a violation of human rights. They wouldn’t listen to me, and said ‘This is the decision made by our company.’ After that interview, I stopped looking for a job.”

Trendyol did not respond to our question about why they did not hire former civil servants dismissed via Decree Laws.

‘IF WE HIRE YOU, WE WILL GET OURSELVES INTO TROUBLE’

Bünyamin Karataş is a former police officer, and he was sacked under a Decree Law published in 2016. He applied for jobs at supermarkets and carpet factories in Malatya, where he lives. He even had friends who recommended him to employers, but nobody wanted to hire a dismissed police officer.

Karataş says, “Almost 99 percent of employers turned me away.” What was the job-seeking process like? Karataş finally landed on a job at Meltem Mobilya, a furniture company, about one month before the Covid-19 pandemic started. But his luck was short-lived.

Karataş gives the following account of what happened: “The manager of Meltem Mobilya in Malatya knew I was dismissed from civil service when he hired me. But the actual boss was living in Istanbul. When he came to Malatya, he scolded the person who hired me, saying ‘Haven’t I told you? Send him away after 20 days.’ When the pandemic started, the person who hired me came and said ‘I’m giving you an unpaid leave.’ I was the first worker that they let go because it was easy. I told them ‘Please, don’t do this. I need to make a living for my family. I need to pay the rent, and I have children,’ but they said the company was not a charity. They didn’t listen to anything I said and fired me.”

In many cases, dismissed civil servants who cannot find a job because of code 37 or who are fired soon after they find a job feel so desperate that they stop looking for a job. However, they need to make ends meet.

After getting fired, Karataş decided to try his chance at ŞOK Market, a supermarket chain. Soon after he submitted his resumé, they called him in for a job interview. He was really hopeful and the interview went very well. Karataş prepared necessary papers and gave the good news to his family. He went to deliver his papers to the manager of the supermarket, who asked for his identification number to register him in the system. A few minutes later, he turned to Karataş and said “We cannot hire you. You were dismissed from civil service according to your SSI records.”

Karataş tried to change his mind, only to no avail: “The manager said to me, ‘If we hire you, we will get ourselves into trouble. Our relationship with the government will go sour.’ I wanted him to give me a written notification, but he didn’t accept this. Therefore, I can’t go to the court. ŞOK Market can check this in their own records. They turned me away because I was dismissed from civil service. Having two university degrees or professional experience is not enough to be considered eligible for a job. I had a misfortune, and now nobody will help me. Everyone will turn me away…”

WHAT DOES ŞOK MARKET SAY?

We called an official at the head office of ŞOK Market and asked why the company doesn’t hire dismissed civil servants. The official said the company will keep that information confidential, and said: “The information under the Labour Code can only be disclosed to the relevant person. The information about which department they will be working at, why they will not be hired, and the procedures and responsibilities related to the job is disclosed verbally to the relevant person. The information about these procedures cannot be disclosed to third parties.”

EMPLOYER: ‘DISMISSED CIVIL SERVANT’ MEANS ‘STOP AND THINK THIS THROUGH’

What do the employers consider when they hire dismissed civil servants? At which stage can they see why the applicants left their former jobs? What do they do when they see an applicant was dismissed via a Decree Law? We ask these questions to employers.

An employer at a company with 7 workers says they first conduct an interview with the applicant. If the interview goes well, they ask the applicant to submit papers for the onboarding process and start preparations to register the new hires in the social security system. The employer says when hiring new people, they check each applicant’s background to see why they left their former jobs: “We can see the historical information of dismissed civil servants in the SSI Registration and Services Page. If a person has been expelled via a Decree Law, this page will show a notification saying ‘dismissed from civil service.’ For employers, this notification means ‘stop and think this through’ because recruiters feel like if they hire these people, they may get themselves into trouble. If you hire a dismissed civil servant, authorities may give you a fine during audits. Unfortunately, many employers take that notification into account when hiring new people.”

Another employer, who owns a digital advertisement and event company and currently has 4 employees, says he does not see it as a problem when he sees the words ‘dismissed via a Decree Law’ in an applicant’s records. However, he still has many concerns when he hires a dismissed civil servant: “First, I conduct interviews to hire someone. Of course, we ask about their previous work experience but we do this only to understand whether the candidate has the necessary experience and competence to fulfil our expectations. If someone was dismissed from civil service, this does not mean that person is unemployable. Of course, it’s important to know why they left their former job. If I see an applicant was ‘dismissed via a Decree Law’, I feel worried because I may be faced with sanctions. However, if the applicant is eligible and a good fit for my company, I will hire that person.”

WHAT DOES THE MINISTRY SAY?

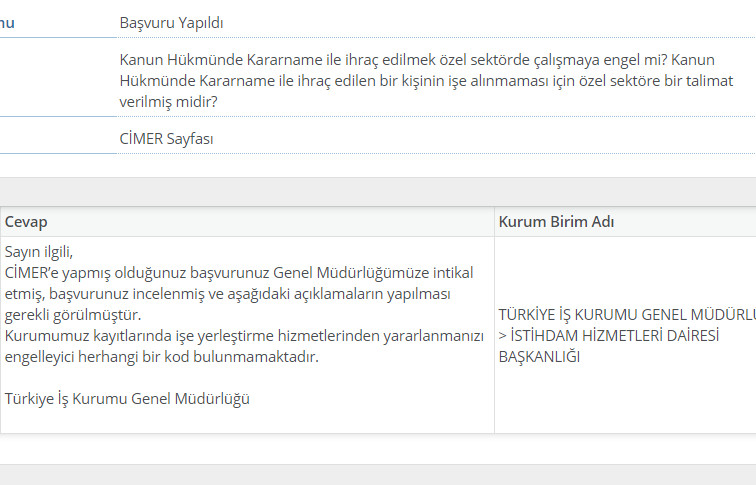

Is there a specific legal provision that prohibits private companies from hiring dismissed civil servants? We contacted Ministry of Labour and Social Security and asked, “Are former civil servants dismissed under a Decree Law prohibited from working in private sector? Have private companies been ordered to avoid hiring dismissed civil servants?”

Officials at the Department of Employment Services at the Directorate-General of Turkish Employment Agency (İŞKUR) argue that there is no prohibition against dismissed civil servants who want to take up jobs in private sector. The response we received from the Department says, “There is not any code in our organization that is used to prohibit access to job placement services.”

MINISTRY OF NATIONAL EDUCATION REVOKES TEACHING LICENSES

Decree Laws have had a more significant impact on specific institutions than others. Expulsions from civil service particularly affected the education sector and schools.

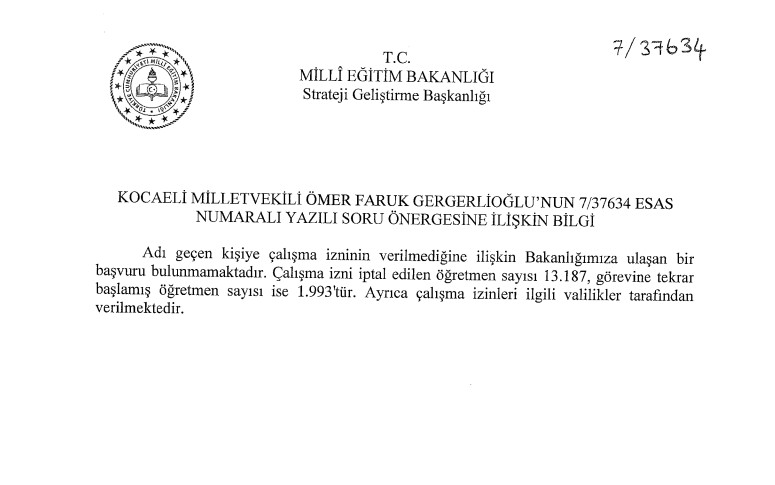

In addition to being dismissed from civil service, teachers had their work licenses revoked, which blocks them from finding jobs at private education institutions. The Ministry of National Education says work licenses of 13,187 teachers have been revoked, including 1,993 teachers who were later reinstated.

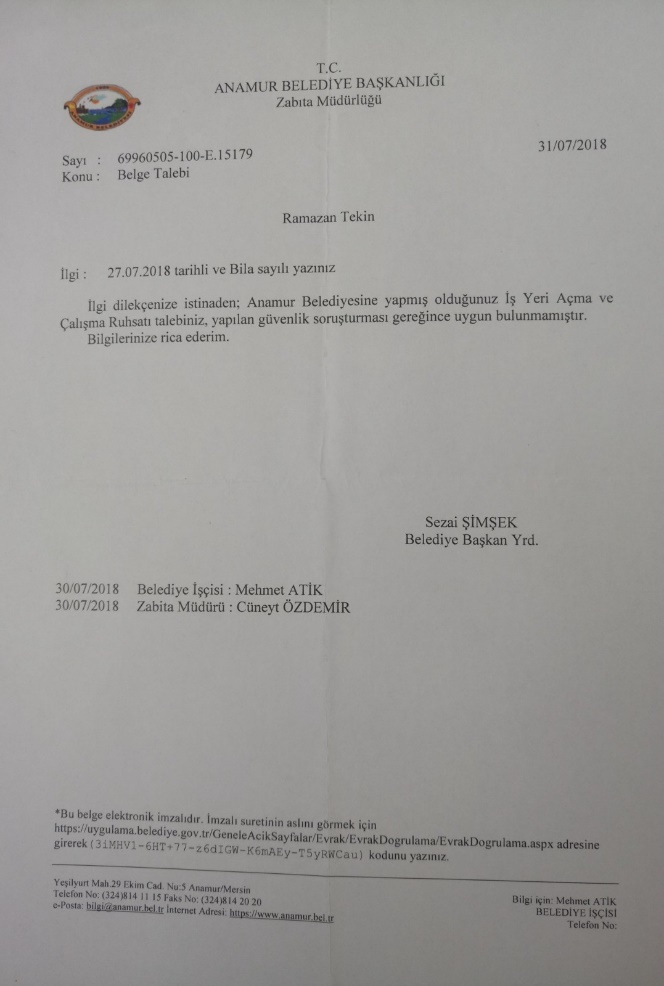

Ramazan Tekin, a dismissed form teacher, is one of thousands of teachers whose work license was cancelled. Tekin’s job-seeking experience has been a little bit different than others. Tekin opened a café in Mersin, but could not get a license for his business for four months. To sort out the problem, Tekin contacted authorities at Anamur Municipality, who told him, “You have a record, so we cannot issue a license for you.” Finally, Tekin received a written notification from Anamur Municipality informing him that his license will not be issued due to the results of the security investigation on his background. Unable to get his license despite all his attempts, Tekin closed down his business.

After several months, Tekin decided to apply to private educational institutions operating under the Ministry of National Education. A private college in Mersin agreed to hire him; however, they decided not to sign a contract with him after they entered his national identification number in the system. Tekin describes his conversation with the officials at the college: “The institution which decided to hire me called the District Directorate of National Education. After that phone call, the institution verbally notified me that they would not hire me.”

After failing to find a job, Tekin started giving private lessons: “Government agencies turn me away when they check my background with my national identification number. I filed an application to İŞKUR but, unfortunately, they haven’t contacted me. They don’t help us. Those who want to help us can’t do it because they are afraid of getting into trouble.”

İŞKUR TERMINATES CONTRACTS OF DISMISSED CIVIL SERVANTS

Like Ministry of National Education, Turkey’s public employment agency İŞKUR, which operates under Ministry of Labour and Social Security, also blocks dismissed civil servants from accessing work license. Many former civil servants who cannot find a job in the private sector apply to İŞKUR, which, on the other hand, has fired all dismissed civil servants it had placed in jobs.

Erkan Özdemir, who was dismissed from civil service in October 2018 under Decree Law no. 701, applied for a job at Sasa Factory via Adana Provincial Directorate of İŞKUR in May 2021. When authorities found out that he was dismissed under a Decree Law, he was fired from his job at the factory only one week after he started working there.

This unwritten policy of blocking dismissed civil servants from accessing to jobs in private sector was also brought several times to the attention of the Turkish parliament by Ömer Faruk Gergerlioğlu, an MP from People’s Democratic Party (HDP).

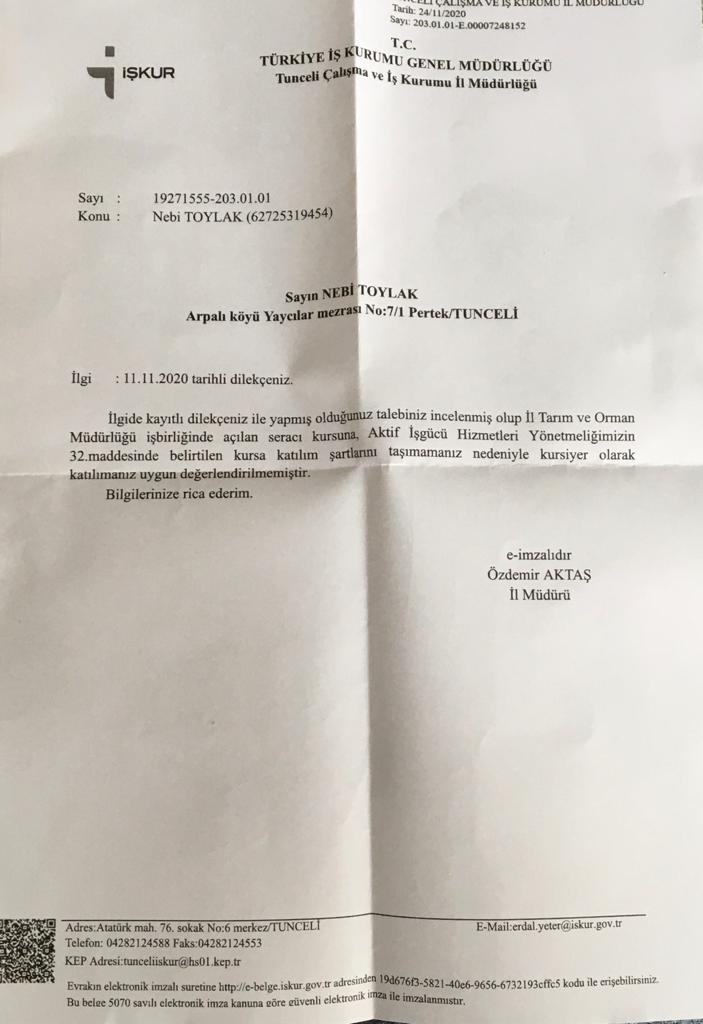

Gergerlioğlu submitted a motion to relevant ministries about what happened to Nebi Toylak, a dismissed civil servant, who was also fired from his job at the greenhouse cultivation course at the Provincial Directorate of Agriculture and Forestry in Tunceli after working there for one week. İŞKUR gave the following response to the motion on November 11, 2020: “You have not been found eligible for the greenhouse cultivation course at the Provincial Directorate of Agriculture and Forestry as you do not have the qualifications for participating in the course as specified in article 32 of the Directive on Active Labour Force Services.”

The article 32 mentioned in the response contains a reference to “circumstances preventing employability.”

COMMISSION ON THE STATE OF EMERGENCY ABOUT TO FINALIZE ALL INQUIRIES

According to the Activity Report published by Turkey’s Inquiry Commission on the State of Emergency, 125,678 civil servants were dismissed after the attempted coup. 35 decree laws were published during the state of emergency, which particularly affected the education sector. In total, 33,597 teachers and 5,925 academics were expelled from their jobs under decree laws. The number of people dismissed from other institutions are as follows: 41,077 from Ministry of Interior, 13,410 from Ministry of National Defense, 7,323 from Higher Education Board/universities, 7,299 from Ministry of Health, 6,994 from Ministry of Justice, 4,384 from Prime Minister’s Office, and 2,491 from Ministry of Finance.

Often criticized for its function and decisions, the Inquiry Commission has so far issued decisions on 126,758 applications from dismissed civil servants who want their jobs back. Only 15,050 people were reinstated by the commission, and 103,365 applications were rejected. 8,343 applications are still pending decision. The Commission also took an interesting step about the applications of Academics of Peace, a group of academics who were dismissed from their jobs at public universities after they signed a petition saying “We will not be a party to this crime” in 2016. Although Turkey’s Constitutional Court has since then ruled that the convictions of the academics violate their rights, the Inquiry Commission has started rejecting the applications of academics. Out of 406 academics who were dismissed, none have been reinstated.

* This article has been prepared in the scope of the “New Generation of Investigative Journalism Training Project” which is implemented by Media Research Association in cooperation with ICFJ (International Centre for Journalists).